What Hath Classical Education To Do With AI, Part II: Curriculum

By Joshua Pauling

In Part 1 of this series, I briefly laid out how classical education, in its assessment and pedagogy, is ready to handle the AI Age. Here in Part 2, I explore how the same is true for a classical curriculum. Robin Phillips and I address the challenges of the digital age for education, home life, the church, society, and more in our new book Are We All Cyborgs Now? Reclaiming Our Humanity from the Machine. Here is a distillation of some of our thoughts on classical education in the AI Age when it comes to curriculum.

Curricular Suggestions

A well-rounded classical curriculum already includes material that can be tailored to address the technological questions we are facing. Below are some possible suggestions in different subject areas.

History – History is a perfect place to tackle the history of technology, so that students learn of humanity’s confrontation with nature and of technology’s impacts on culture and society. Neil Postman frequently argued that by making technology itself an object of inquiry, students end up “more interested in asking questions about the computer than in getting answers from it.” Consider all the fruitful debates, essays, speeches, Socratic discussions, and lesson plans that could examine the tradeoffs brought about by advancements such as the car or the phone, the mechanical clock or electricity, industrialization or urbanization. And by facilitating these types of deliberations, we also provide students with a framework for considering the tradeoffs of new technologies like AI as well.

Math, Science, and Logic – Here might be the place to dig into how AI tools and large language models like ChaptGPT actually work. Demystifying the technology, as Gene Callahan does so nicely here, helps reduce its allure, and by potentially bringing in AI as an object of inquiry, it is taken out of the realm of things forbidden, which could reduce temptations for misuse as well.

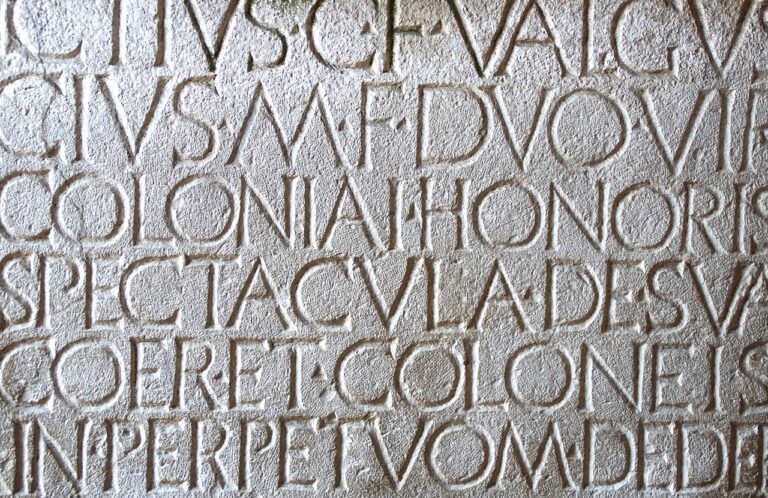

Philosophy and Theology – AI and digital technologies cause us to grapple with philosophical, anthropological, and theological questions that, for many students, may have previously seemed remote. The mind-body problem, the epistemic virtues, the meaning of being human, the nature of consciousness, and the difference between computation and knowledge all rush to the forefront in the age of AI. Texts like Plato’s Republic, Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Descartes’ Discourse on Method, Heidegger’s The Question Concerning Technology take on fresh relevance.

Consider Plato’s Phaedrus, where King Thamus warns of the unintended consequences of the technology of writing:

This invention of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners’ souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves….They will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome, having the reputation of knowledge without the reality.

Philosophical questions also require us to ask theological questions, which we can address with Scripture and the resources of our theological traditions, bringing us into further explorations like this: What does Scripture say about technology? Do the city of Man and the city of God relate to technology differently? How is the Tower of Babel a story of technological hubris? How does God redeem technology in the construction of the Tabernacle and Temple, and ultimately in the promise of the New Jerusalem?

Literature – Once you start reflecting on the great works of human civilization, you begin to see how central the question of technology has been throughout history. Below is a sampling.

The Greek Myth of Prometheus – Prometheus steals fire from the gods, and brings to mankind technological advancement, becoming the symbol of mastery and control. (And don’t forget about his lesser-known younger brother Epimetheus!)

The Odyssey, Homer – Some of Odysseus’ temptations, particularly with Calypso and Circe, are enticements to reject his humanity and enjoy a life of ease, relaxation, and even immortality. But he ultimately chooses human risk, love, and even death as he returns to Penelope.

Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift – Amid the satire, Swift offers some powerful fictional examples of the sway of technology on our lives as Gulliver visits different islands.

Frankenstein, Mary Shelley – Also entitled The Modern Prometheus, it is the tragic story of Victor Frankenstein’s technological grasping for godlike status in creating an artificial being.

The Machine Stops, E. M. Forster – A vision of the future in which human beings can no longer live on the surface of the earth, but instead live underground within a machine network that provides air, food, water, entertainment, and all their other needs and wants at the push of a button.

The Lord of the Rings, J. R. R. Tolkien – In additional to many other themes, there is an underlying critique of industrialization, mechanization, and dehumanization in the depiction of Mordor, the Orcs, the destruction of the forest to fuel their forge to craft weapons, and all of this is in sharp contrast to the lives of the Elves and Hobbits.

Brave New World, Aldous Huxley – A complacent society is kept subservient through an elaborate administration of comfort and pleasure through drugs, sex, and other forms of escape that deadens them to any higher goods.

Conclusion: Human Wisdom is More than Computation

As the AI Age unfolds, we must remember that knowledge and wisdom are different from computation. Knowledge and wisdom are embodied and are much more than inputs and outputs. They are slow. But that slowness, that strain, that challenge, is what forms us. The book of Proverbs paints just such a picture of wisdom, where the wise man attends to the way things are and delights in God’s Word. The wise man is not someone who can compute the fastest or knows the right facts, but one whose affections have been properly ordered, bringing knowledge of truth into wisdom in action. Wisdom comes to appear not only right and true, but beautiful and desirable (Pr. 3:15-18).

The development of virtue occurs through the long process of learning and living. To put it succinctly, do we want to shape the type of people who push a button to listen to Bach, who have a chatbot write them a poem, who have an image generator paint them a picture? Or, do we want to form the type of people who can play Bach on the piano, who can revel in writing a poem, who can create art with their own hands? Are these mutually exclusive? Where should the line be drawn? Is there a certain threshold of artificiality that we cross after which our abilities and capacities begin to atrophy? And have we already crossed it? These are the types of questions we need to put our best minds and efforts towards answering clearly, because such questions aren’t just coming; they are already here.

While there is still work to be done on precisely defining the relationship between AI tools and education and where to place the exact boundaries, we must have a clear answer ready for when a student asks “Why shouldn’t I have AI write my paper?” Perhaps a pithy response would be thus:

Because you’re outsourcing your humanity to a machine. For the same reason you shouldn’t cheat on a test or plagiarize. Because you’re not learning; you’re offloading the process to an algorithm and are taking the easy way out. It’s like watching a robot lift weights for you–you gain nothing from it. Learning entails risk, challenge, strain, difficulty, and it is through such things that you build wisdom, virtue, and patience—that you become a better you.

And perhaps this is the most insidious danger with AI technologies in relation to education: they offer the false promise that you can skip the kinds of effort and hard work that actually develop the human capacities we need for a full and flourishing life. If we buy into this false promise, I fear it is we who end up being deskilled, we who atrophy, we who lose the capacity to exercise those gifts (we might never learn what our gifts are in the first place), gifts that are only embodied through struggle and exercise. This is precisely what the great farmer-poet Wendell Berry warned of in his 2001 book Life is a Miracle: “the next great division of the world will be between people who wish to live as creatures and people who wish to live as machines.” Education is the perfect place to treasure our lives as creatures and practice living as creatures, as human beings, fully alive and in relationship to one another. Education’s end goal is not grades, credentials, transactions, or computations, but the formation of full and whole persons.